There are two books on the art and craft of writing that really resonated with me at the time I read them and have also stayed with me over the years. I have read many other writing advice books, but these two always come to mind whenever the topic of good books on writing happens to come up. (Okay, yes, that is fairly rare, but it does happen.)

On Writing by Stephen King

On Writing is part memoir, part writer’s manual. Since it’s written by King, you would think it would be about how to write horror, but it’s about the craft of storytelling as a whole.

Key Takeaways:

“Write with the door closed, rewrite with the door open.”

King emphasizes that the first draft is for you and it doesn’t need to be pretty. The second draft is when you start thinking about the reader.

Cut 10% in revision.

Concise writing is clear writing. He suggests trimming your drafts ruthlessly.

The toolbox metaphor.

King encourages writers to build a mental “toolbox” of grammar, vocabulary, and style and to always keep adding to the toolbox.

Read a lot, write a lot.

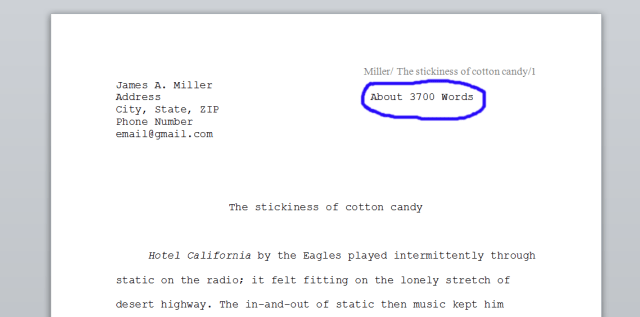

King reads constantly and writes daily. He shoots for six pages every day, which is a pace that left even George R.R. Martin stunned. Most writers are not quite that prolific.

Let the story drive the plot, rather than outlining everything. This is not for every writer and gets into the whole Pantser vs Plotter discussion (probably a good topic for another blog post). King is a Pantser, he creates the characters and follows them around. This may also be why I am not in love with his endings.

Adverbs and the passive voice, One specific item that stayed with me from On Writing was to eliminate the use of adverbs and the passive whenever possible.

How to Write Science Fiction and Fantasy by Orson Scott Card

Card’s book is a short, easy read, and one that I couldn’t put down.

Key Takeaways:

World-building starts with what must be true.

Card argues that you don’t need to create a full encyclopedia before writing your story, you just need to know the parts that matter. The ripple effects of one change (say, faster-than-light travel) should shape your entire setting and culture. I really liked how he walked through his world-building technique. It was like I was right there with him as he drew out a map on a big sheet of paper, somewhat randomly placing the world objects, then came up with reasons for things to be the way they are and the implications behind them. I am being intentionally vague as to not give too much away.

Know your story’s “moral premise.”

Even in genre fiction, your story has a core theme or question. Knowing it gives you a compass for plot, character, and tone. This is also somewhat controversial. Some would argue that the only purpose of fiction is to entertain. Others insist that fiction must have some purpose, often to reflect life and make us think. I probably lean more toward the entertainment side of the argument, but I also think that entertainment serves a purpose.

Milieu, character, and event stories.

Card’s MICE (Milieu, Idea, Character, Event) model helps to identify story type, basically where it should start and end.

- A Milieu story begins and ends with entering and exiting a world.

- A Character story revolves around transformation.

Don’t be afraid to play within the genre but know the rules first.

Card encourages innovation after understanding reader expectations. If you’re going to bend the rules, do it on purpose because you understand where the lines are to begin with.

The cost of magic was an interesting concept I hadn’t thought about prior to reading his book. It basically means that there must be some price for magic or characters essentially become gods.

Do these books on writing stand the test of time?

I am not sure if these books would have resonated with me the same way today as they did back when I initially read them, probably 20 years ago now. They were certainly right for me at the time, but I do think the advice is solid and still applicable. If you’re serious about writing speculative fiction, these two definitely deserve a place on your shelf.

Let me know what you think. Are there any books on writing that you found particularly useful or resonated with you?

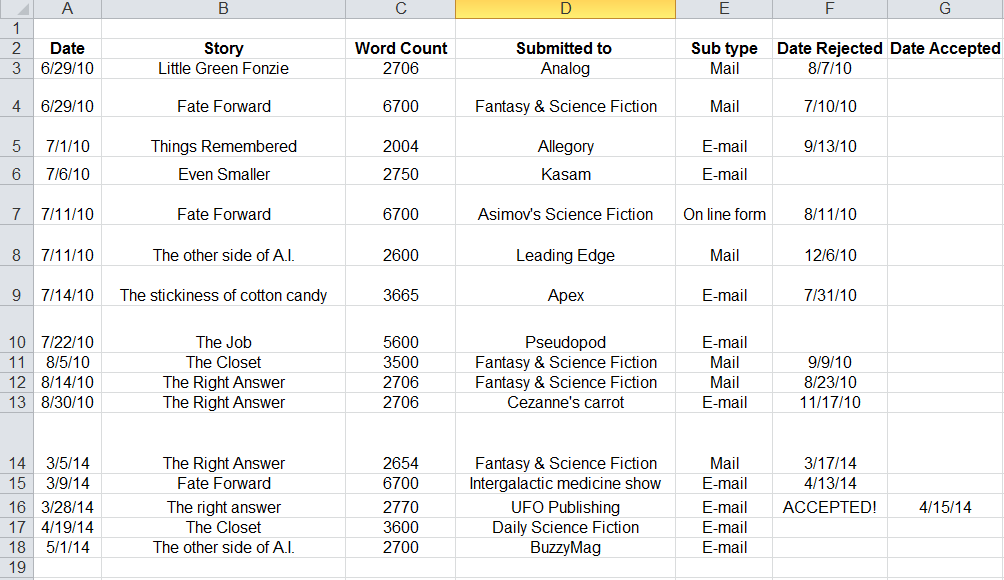

-James

Note that I linked to where the books are available on Amazon, but you are better off hitting the library or trying eBay. Buying books from eBay and reselling them back is one of my favorite non-library ways to get books. I like the option of keeping it for a long time and not having to remember to return it.