This week we have a non-fiction guest post from Y. Len.

Sticking withe the theme of this Blog Y Len’s non-fiction post has been [mistakenly] rejected by CRAFT, Writers Digest and Authors Publish.

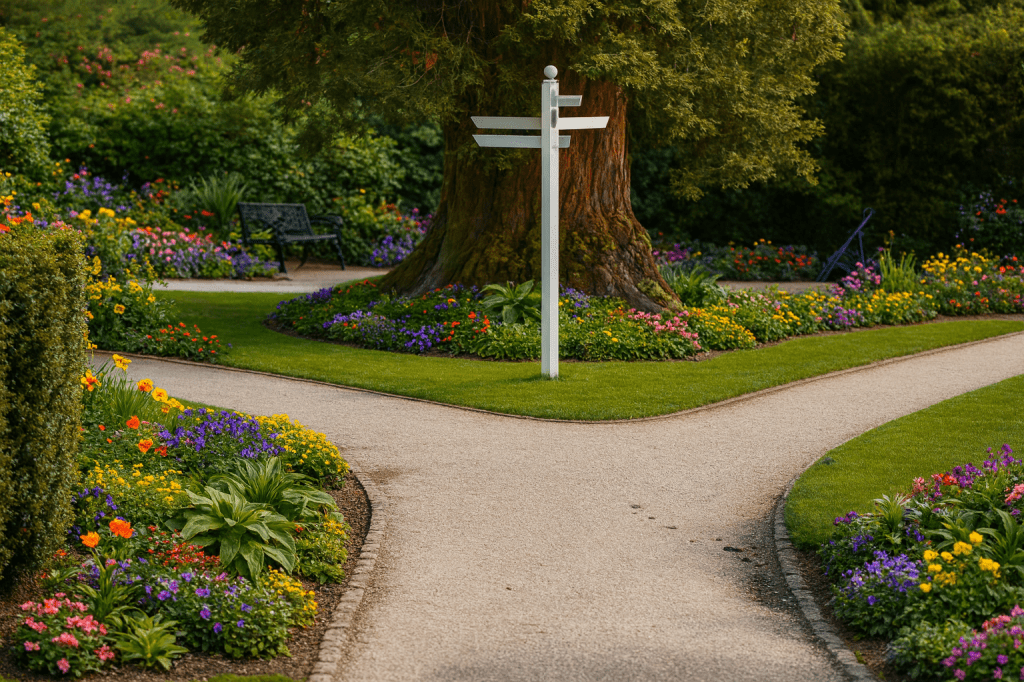

On the F***ing Garden Path in Fiction, by Y. Len

To a reader:

Note 1: The word in the title that caught your attention is “Forking” and NOT what you thought;

Note 2: Contrary to what you may be thinking now, this isn’t about Borges’s “The Garden of Forking Paths”;

Note 3: Read on if you consider yourself a contrarian. If garden variety sentences are your cup of tea—fork off onto your own path.

Garden path sentences are a tricky kind of phrase

They lead you to a dead end as you try to parse their ways

They start with words that seem to make a clear and simple sense

But then they twist and turn and leave you hanging in suspense

The rules of writing castigate garden path sentences—what better reason for taking a closer look and perhaps using them to break into the craft?

A garden path effect in writing is achieved by weaving a semantic ambiguity into a sentence. While being read, the sentence leads the reader toward a seemingly familiar meaning that is actually not the one intended. That’s where/how the “forking” happens. When read to the end, the sentence seems ungrammatical or makes no sense and requires rereading so that its true meaning may be fully understood after alternative parsing.

The horticultural label for this linguistic phenomenon hails from an old saying “to be led down (or up) the garden path”, meaning to be deceived, tricked, or seduced. In a century-old “A Dictionary of Modern English Usage” (1926), H.W. Fowler describes such sentences as unwittingly laying a “false scent”.

In late 1970s–1980s, Lyn Frazier and Janet Dean Fodor developed the “Garden Path Model” of sentence processing. It argued that readers use simplest-structure-first heuristics. When those heuristics fail, readers experience the garden path effect. Later research argued that multiple cues (syntax, semantics, context, frequency of usage) all interact.

The old man the boats. The old man… here is first taken as a noun and a verb is expected next. Correct parse: The old [people] man (verb) the boats. This popular example illustrates how word class ambiguity (noun vs. verb) tricks the reader.

The horse raced past the barn fell. The horse raced past the barn… here feels complete. Correct parse: The horse [that was] raced past the barn fell. This, one of the most cited examples in the literature, shows how readers “commit too early” to a sentence structure and must re-analyze.

Fat people eat accumulates. Similar to the above example, intentional missing relative pronoun (that) prompts misanalysis.

Hard to argue the “expert” opinion that garden paths have no place in academic, technical and business writing where clarity rules. In case of fiction in general and certain genres of fiction in particular, the answer may not be as straightforward.

The optimist in me believes that not all readers are content with garden variety sentences. Some may enjoy cracking open verbs and nouns to attribute agency where others wouldn’t expect it, and/or stringing together phrases that tell stories with their structure, as well as with their content. Yes, the complex prose demands a mental effort when constructing the images or navigating the linguistic possibilities that it presents. Yet the payoff of doing so is (i) the immediate satisfaction (“Aha! That writer ain’t no slouch, but I got it anyway!”) AND (ii) an expansion of the boundaries of language and the enrichment of what one can imagine on the page.

Remember your inexplicable affinity for that IKEA piece you put so much time and frustration into putting together after putting so much time and frustration into understanding the accompanying instructions given in tiny font in multiple languages with English seeming only slightly less bewildering than the others? Similar satisfaction may result from reading “some assembly required” prose.

Another off the cuff example would be Hitchcock’s films that make the audience jump to conclusions that are inevitably incorrect. Doesn’t a garden path sentence do the same on a micro level? By momentarily misleading the reader, it can create a sense of mystery and intrigue.

At their core, garden path sentences manipulate the reader’s expectations. They present a surface meaning that sooner or later collapses under grammatical or semantic pressure, demanding rereading and rethinking. This small act of disorientation can be scaled upward: in fiction, a writer might mirror a character’s confusion, instability, or unreliability through similar linguistic detours.

For instance, in a psychological thriller, sentences that shift direction can echo a protagonist’s fractured mental state, forcing the reader to share in their uncertainty.

In my adventure/murder mystery “The Bloodvein River Monster,” the adult character is recovering from mercury poisoning that affected his mental ability.

The five-year-old boy with the runny nose woke thirsty and lay in the dark, listening to silence. No flashing colors, no frightening voices in his head. A clean scent of resin and wood told him where he was and that he was no longer that boy.

He had no idea how long he’d slept, only a vague memory of stumbling through the forest. It was still night. Or already? His body felt weak, but there was no panic. Thoughts drifted, bumping softly one into the other, yet he could hold on to them long enough to finish each before the next arrived. He scooped handfuls of snow into his mouth, the chill numbing his tongue but easing his thirst, and drifted back into sleep.

Next time Ezra woke with the feeling the dream left.

The last sentence of the excerpt carries the drifting, dreamlike atmosphere established earlier even after the character wakes—the garden path phrasing itself is deliberately ambiguous (Ezra woke, feeling that the dream has left or he woke with some unspecified feeling left by the dream?) inviting the reader to share in Ezra’s uncertainty. The psycholinguistic effect of a single short sentence here is comparable to that of the entire first paragraph that achieves the similar result as it starts with the character as the five-year-old boy only to end by denying that very fact.

The garden path technique also offers rhythmical and aesthetic value. “Traditional” prose strives toward clarity, smoothing the reader’s ride over the (often intentionally) bumpy roads our characters take. By contrast, garden path structures may introduce hesitation and slower reading, break immersion and compel attention to the mechanics of language itself.

The last but not least, garden path sentences can serve as thematic devices. Stories about deception, shifting identities, or supernatural interference gain resonance when their very sentences enact misdirection. The language performs the subject matter: just as a character may be fooled, so too is the reader. In this sense, garden paths may become not just ornamental puzzles but enactments of the story’s underlying concerns.

Of course, as with almost everything in life, restraint is essential. Overuse your rake in your writing and you’ll risk reader’s frustration, turning prose into a riddle rather than a narrative. But strategically placed—like a topspin serve à la Pete Sampras in your otherwise bland pickleball game—a garden path sentence or two of them can create surprise, deepen psychological realism, and remind readers that language itself is a valuable writer’s tool.

Have fun in the garden!

Garden path sentences are fun to read and write

They challenge your grammar and the depth of your insight

They show you how the English language can be full of tricks

And how a single word can change the meaning in a flick

It’s an excellent literary device for mystery or for humor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for reading and commenting.

LikeLike

What an eye-opener. Thanks for the clear and concise explanation.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Informative and entertaining, thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is very interesting. My first reaction was that they would be more suitable for poetry than fiction, but your examples show how they could be useful for creating ambiguity.

LikeLiked by 1 person